![]()

To Scorned Woman . . .

May 18, 1980 dawned clear and bright. It was an amazingly beautiful day for May in the Pacific Northwest. Being a Sunday, there were only a few loggers, campers and scientists in the area. Many of these people had been lulled into a false sense of security because of the mountain's recent silence. Not even the scientists could predict exactly what was to come.

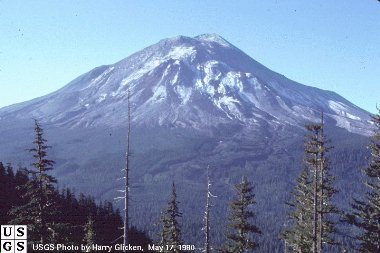

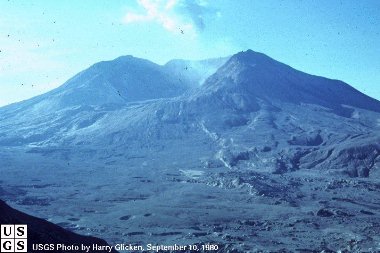

Both of the pictures below were taken from Johnston Ridge, just 5 miles northwest of the summit. It was here that U.S. Geological Survey vulcanologist, David Johnston, was taking measurements the morning of the 18th. At 8:32 a.m. (PST), Johnston radioed "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!", only moments before he was struck by the advancing wall of rock, ice and trees that swept laterally from the mountain at more than 500 miles per hour. His body has never been found. In May of 1997 an observation and education center was built on Johnston Ridge in his honor. It is the visitor's center closest to the mountain. (photos below by Harry Glicken, USGS)

At 8:32 a.m. a 5.1 magnitude quake struck one mile below the mountain. While there had been literally hundreds of earthquakes at the mountain since March 20th, the unstable north face could not sustain another. Within moments the largest landslide in recorded history removed more than 1,300 feet from the summit and swept away almost the entire north side of the mountain. The elevation of the mountain dropped from 9,677 feet to its present day 8,363 feet. What was once the 9th highest peak in Washington state was suddenly reduced to the 30th highest peak. The intense high pressure/high temperature steam that escaped, instantly turned more than 70% of the snow and glacial ice on the mountain to water. This massive movement of rock, ash, water and downed trees swept into Spirit Lake and down the north fork of the Toutle River Valley at speeds in excess of 175 miles per hour.

As the north face slid away it let loose the trapped gases like a cork removed from a well shaken bottle of champagne. The three pictures below are from a series of photos taken by Gary Rosenquist who was camping at Bear Meadows, 11 miles north east of the mountain. Rosenquist and the rest of his party survived the eruption even though the lateral bast was rushing straight in their direction at speeds nearing 650 miles per hour. Luckily, after rolling over ridge after ridge, the blast suddenly turned. In the last picture you can see the lateral blast overtaking the landslide. In only three minutes the blast flattened 230 square miles of old growth forest in a fan shape north of the mountain.

Mt. St. Helens is on an ocean-continent subduction boundary (the Juan de Fuca plate is subducting under the N. American plate). Mt. St. Helens is an active strato volcano. The easiest answer to what caused the eruption is that a body of magma moved into the shallow part of the volcano between the first earthquakes and minor eruptions in March, and by May 18th had become so pressurized that the north face of the mountain failed and this magma was able to erupt.

The slow moving collision of the continental rock of North America and the Oceanic Rock of the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate, which is slowly moving beneath the Pacific Northwest is slowly refueling Mount St. Helens for another eruption. Scientists estimate that there is a large reservoir of magma four miles beneath the crater. No one knows enough about the volcano to predict when it will erupt again or what kind of volcanic activity the next eruption might bring.

|

|

|

![]()

The eruptions effects were far reaching . . .

| As the north face of the mountain collapsed, expanding gases and steam

from the molten rock hurtled rock and ash out across the land at speeds up to 670 miles

per hour uprooting trees as far as 6 miles from the mountain. It was impossible to

outrun and the searing heat too intense. Reid Blackburn, a photographer with The

Columbian newspaper was one of the first victims of the eruption. Blackburn had

tried to take shelter in his car but the lateral blast blew in the windows, letting in the

hot, choking ash. He was found in his car 7 miles north of the mountain. (photo by Daniel Dzurisim) For more information regarding the 57 people who were killed, please see my Eruption Victims page. |

|

|

Along with the loss of human life, it seemed the plants and animals in

the area were almost completely wiped out as well. It is estimated that 5,000 black-tailed

deer, 1,500 Roosevelt elk, 200 black bears, and 15 mountain goats fell victim. Millions of

small game, fish, birds and insects were also in the path of the eruption. The areas nearest the mountain were completely stripped of topsoil by the lateral blast. Nothing remains but bare rock. For weeks after the eruption, pyroclastic flows (seen here at left) of escaping steam and ash rolled down the remains of the north face, sterilizing the soil with its intense 1200 degree heat and depositing pumice and ash up to 60 feet thick in the valley below. Two weeks after the eruption when temperature measurements could safely be made, the pyroclastic deposits still averaged 650 degrees. Today, the pumice plan, a fan shaped area just below the crater, has been heavily eroded by wind and rain. |

| Directly in the path of the huge landslide was Spirit Lake. Normally a chilly 42 degrees, the landslide instantly raised the temperature to near 100 degrees. As the mud and rock hit the lake, the intense temperatures and choking ash killed all of the life in the water. Like dropping a large rock into a bucket of water, the lake sloshed up onto the surrounding hillsides, pulling trees and other debris into the lake. With the addition of heavy metals from the mountain and all the organic material washed down from the hillsides, huge bubbles of methane gas escaped from the lake for months after the eruption. Today the bottom of Spirit Lake is 100 feet above the original surface. The lake now has two and a half times more surface area than it did before the eruption. This photo was taken from the top of Mt. St. Helens looking north. Mt. Rainier can be seen in the distance. (photo to right by Lyn Topinka, USGS) The water in the lake looks strange because there is a gigantic mat of logs floating on the surface. Today many of these logs have sunk or washed up on shore. Plants and small animals are slowly returning to the water but so far the water is still not able to sustain larger life such as fish. |

Spirit Lake retains it's odd mitten shape but now lies nearly lifeless and full of barkless, sunbleached tree trunks. As the logs become water logged, they sink root-wod first and settle on the bottom. Divers have spoken of swimming among an eerie "ghost forest" on the bottom of the lake bed approximately 150 feet below the surface. |

|

The larger portion of the landslide flowed down the Toutle River Valley at speeds of 30 miles an hour at times carrying rock (some boulders were as big as 20 feet in diameter), ash, trees and even homes downstream with it. Twenty-seven bridges were destroyed by the 25 foot tall wall of debris. By the evening of the 18th, the Army Corps of Engineers was forced to close the Columbia River at Longview, more than 75 miles from the mountain. The normally 40-foot deep channel had been reduced to 17 feet by ash sediment washed downstream. Even after six days of dredging, large freight ships could only navigate that section of the river during high tide "windows" when the channel was 30 feet deep. Even now the remains of the debris avalanche sends enough sediment down the river that it is a muddy brown and towns and cities downstream can flood if the sediment retention dam can not retain enough of the silt. |

The people around the mountain began their clean-up efforts almost immediately. To the amazement of scientists studying the effects of the eruption, Mt. St. Helens began cleaning up as well.

![]()

| An Eyewitness Account by John H Lienhard It was a beautiful Sunday, morning in the Pacific Northwest. I left my home in Walla Walla, WA, to drive to Pendleton, Oregon, airport. As I drove south crossing the Washington-Oregon border the sun was rising over the Blue Mountains. It was a perfect day for my trip to Newark, N.J. via Portland and Chicago. I was booked on United Airlines Flight No. 271, scheduled to depart from Pendleton at 8:00 AM and arrive in Portland at 8:39 AM. As I recall we were a few minutes late in departing. The aircraft for the flight to Portland was a 727. A few days before, Mt. St. Helens had given an indication of activity with tremors and emitting of gases. Taking this in consideration, I took a window seat on the right side of the aircraft. My purpose being that I wanted to get a good view of the mountain when we flew past. There were probably no more than 20 to 25 passengers on board that morning. The flight originated in Pendleton and most of the passengers were to connect with other flights out of Portland. Soon after leaving Pendleton we were flying west parallel to the Columbia River. It was a bright and cloudless sky and the morning sun glistened on the snow cap mountains of the Cascade Range. Somewhere in the vicinity of Mount Hood, OR our plane crossed over the Columbia River and proceeded in a westerly direction on the Washington side of the River. Our pilot was starting to descend to make the landing in Portland. Looking out the window I could see that we were approaching the vicinity of Mt. St. Helens. Soon we were directly south of the mountain. The sky was very clear and an occasional white cloud but nothing to obstruct the view of the mountain. The pilot started to explain to the passengers and said; "There is Mount St. Helens, she has been rather quiet the past few days". At that point most of the passengers had moved to the right side of the plane to get a better view. The plane was at an altitude on the decent to Portland airport that provide those on board UAL 271 a view of not looking down at the mountain but rather out at the mountain. Although, we were possibly higher than the mountain peak, it appeared that we could almost reach out and touch it. I took my eyes off of the mountain and leaned back in my seat. In a matter of seconds the pilot shouted over the speaker: "Everyone look quick, Mount St. Helens is making a spectacular display". At that point, all of the passengers rushed to the right side of the plane and we saw an unbelievable sight. What had been a rather tranquil landscape only moments before had become an almost indescribable scene. A plume of black ash immediately exploded from the mountain and went straight up into the atmosphere. I have no idea how high the plume went only to know that the ascent was very rapid. (At a later time, a United Airline pilot approaching Portland from the south indicated it went to 90,000 ft.) Simultaneously, it appeared that the westerly part of the mountain exploded and the area and sky were dark with the deep gray to charcoal black ash. In a few minutes we were landing at the Portland airport. The sky was not a clear blue that was evident before the eruption but rather a hazy yellowish hue. There was a certain odor in the air that may have been a sulfur odor. As the plane taxied to the terminal building, I was making my plans for the next flight I was to take. I knew that to get the best view of the mountain I should get a seat by the window on the left side of the plane. After arriving inside the terminal I quickly went to get my seat assignment on United Airline Flight #152, scheduled to depart at 10:30 AM for Chicago. The terminal was generally a quiet place that Sunday morning. I talked with several people at the United Airline counter and none of them were aware of what Mt. St. Helens was doing and seemed very surprised. Looking east from the terminal building, one could see the black cloud moving to the east. It was very evident that prevailing winds were out of the west and thus moving the cloud of ash in an easterly direction. I do not recall if UAL flight #152 departed on time but it was not delayed very long if at all. Little did I realize what I would see on this leg of my journey. As the passengers boarded and were seated, it was amazing to me how few of these people were aware of the eruption of the mountain. Likewise, they were not prepared for what they would soon see. After the plane was airborne and was on course to the east we could see the mountain. At that time the pilot announced: " Mt. St. Helens is erupting and therefore our flight plan calls for us to stay just south of the Columbia River and maintain a low altitude until we are certain that we are away from the cloud of ash." The pilot continued to describe the eruption of Mt. St. Helens and indicated he would fly as close to the south side of the Columbia River that he considered safe. The mountain was belching ash and smoke and was very dark and eerie. There appeared to be lightning flashes coming from the crater. The reaction of the passengers was one of excitement to one of no interest. I recall that two ladies from Portland were sitting in my row of seats. Most of the people from the other side of the aisle were practically on top of those of us on the left side so they could get a good view of the mountain. The two ladies were busy chatting away at what they were going to do in New York. I asked them: "Do you see the mountain erupting?" Their reply after viewing the mountain at a glance was one of amazement. "I have never seen a mountain do that before." At the time I thought the explanation was a gross understatement but after thinking about it, I had to agree. Soon our plane was out of sight of St. Helens --but that cloud was parallel to our flight path. Our plane was on the Oregon side of the river and the cloud was on the Washington or north side of the river. As our plane continued east our pilot continued to comment. He would say; "We are now passing Hood River and the cloud is still with us." Then later; "We are passing The Dalles and the cloud is still with us." This continued to be repeated until we were in the vicinity of Hermiston, Oregon. At that point the cloud of ash picked up a wind out of the southwest and it made a sharp turn to the north toward Tri-Cities, Moses Lake and Spokane, Washington. As I continued to keep my itinerary and call on my customers, I found myself repeating this story over and over. I was questioned repeatedly about what I had experienced. The interest was very high at the time. As a point of information: As I was told on my arrival in the East, our flight from Portland was one of the last out of the Northwest on that Sunday. The airports were closed down and flights were suspended. The fine ash was entering aircraft, truck, automobile and locomotive engines and the abrasive action was causing great damage. That is the end of my story. I still have my United Airline tickets along with memories. I appreciate being able to share this story. John H. Lienhard (written August 27, 2000) |

![]()

Pages designed May 1998 by Valerie A. Smith. Please send all

questions, comments and suggestions to valerie@olywa.net

Thank you to the USGS and other featured photographers. Without the photos, these

pages would not be possible.

This page last updated

June 06, 2006.